Written by: Rebecca Berman, LCSW-C, CEDS-S, MLSP

Clinical Training Specialist

Autistic and neurodivergent eating disorder patients often receive treatment developed and managed by neurotypical professionals. But how does this impact their experience and recovery trajectory?

Autistic and neurodivergent eating disorder patients often receive treatment developed and managed by neurotypical professionals. But how does this impact their experience and recovery trajectory?

“Nothing about us without us.”

The above slogan is commonly used to communicate that no policy – including treatment interventions – should be created without the full and direct participation of members of the group impacted by it.

Historically, the development of diagnoses, research, treatment interventions, etc. for neurodivergent people have been developed by neurotypical individuals – including for the treatment of eating disorders.

Without an awareness and commitment to understanding difference, neurodivergent patients with eating disorders are at risk of preventable adverse events in mental healthcare, including an increased risk of trauma, marginalization, and microaggressions.

But before we look at why, let’s be clear on what we mean by “neurodivergence.”

What is Neurodivergence?

Below are some terms we think would be helpful to know as we go through this blog.

Neurotypical: Refers to an individual with typical neurological development and functioning.

Neurodivergent: Refers to an individual whose brain develops and functions differently than the norm. While the term can be used to encompass other conditions, including mental illness, it will be used here to refer to Autism and ADHD, which naturally develop from birth or very early childhood.

Autism: A neurodevelopmental disability that affects how people think, feel, communicate, move, socialize, and perceive and experience the world around them.

ADHD: A neurodevelopmental disability that interferes with executive functioning, and characterized by patterns of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. Many traits overlap with autism.

Neurodivergence & Eating Disorders: What We Know

While we are learning more about neurodivergence and eating disorders, little is known and much more research is needed.

“Research suggests that up to one in four individuals with anorexia nervosa (AN) may be on the autistic spectrum, and that these autistic traits may not have been recognized or diagnosed prior to eating disorder (ED) treatment. Significantly, these heightened autistic traits are associated with poorer treatment outcomes, suggesting that treatment may need to be adapted for this population” (Kinnaird, et al., 2019).

Other research estimates that the co-occurring of Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID) and Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) ranges from 12.5% up to 33.3%. (Harris et al., 2019; Inouye 2021)

One thing we know for sure: While neurodivergent individuals may experience all types of eating disorders, the two most prevalent are anorexia and ARFID.

Additionally, autistic people are significantly more at risk of experiencing suicidal thoughts, behaviors, and death by suicide.

Defining What We’re Treating (& What We’re NOT)

When we think about interventions and treatment goals, it is important to remember we are not trying to give autistics skills to lessen their autism. We are working with them and their autism by adapting our treatment approach to meet their specific needs.

Cessation of eating disorder symptoms may be a goal. However, to no longer be autistic is not the goal of treatment and not possible. It may be difficult to know if someone is autistic because of the high likelihood that the individual is “masking” and therefore feeling less safe in their community.

Masking occurs when individuals learn, practice, and then perform certain behaviors (while also suppressing others) to appear more like those around them (neurotypicals).

How Trauma-Informed Care Can Help

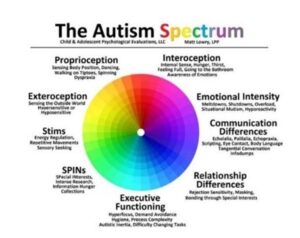

There are many different things that contribute to the autism spectrum.

If we think of it as a music board people will have different parts that are dialed up while others are dialed down. The music board, however, changes throughout the day based on things like energy, support, resources, stress, and other antecedents.

All of the different parts, which can be seen in the image below are important to understanding an autistic person’s experience.

As we think about trauma informed care, it is essential to recognize different experiences of intersectionality. It’s important to consider treatment and recovery from an anti-oppressive lens.

Many neurodivergent individuals occupy multiple marginalized identities, and the work on the eating disorder cannot be separated from the work on the effects of systemic oppression. It is important to consider how systemic oppression affects the individual person – in their life, in treatment, and in their eating disorder.

To treat the whole individual, it is essential to learn about the patients’ culture, identity, and neurodevelopmental differences. In fact, many neurodivergent individuals have experienced trauma from the systems they have been in. This includes treatment trauma.

We have an obligation to our patients and to each other to increase our knowledge about neurodivergence so that we can adapt our treatment approach to meet the needs of the patient.

To that end, here are a few important considerations treatment providers should understand before treating patients.

Essential Considerations for Treating Neurodivergent Eating Disorder Patients

‘Stimming’

When working with neurodivergent individuals it is necessary to understand the concept of stimming.

Self-stimulation (aka stimming) helps with sensory processing and may aid in communication. It can be a way of releasing tension and energy.

Stimming activates neurotransmitters that regulate emotions, like dopamine, serotonin, and glutamate. While stimming typically refers to repetitive movements, it can also include staring at stimuli (such as lights) or making sounds (noisemaking or humming). Commonly associated with ASD – hand-flapping, rocking back and forth, or repeating sounds or phrases.

“People who stim are communicating, and when you restrict stimming, you’ve removed an avenue for them to talk about their experiences,” according to clinical psychologist, Dr. Fizur (Rowello, L. 2022).

Stimming can help with overstimulation, under stimulation, emotion regulation, communication, pain management, stress relief, and pleasure. Treatment should involve approaching with curiosity and understanding.

It is extra important that we explore with a patient whether the behavior is being used as avoidance or whether it is a stimming behavior to bring them to a place where they can process the emotion. A behavior can change and may have a variety of purposes so it’s important to keep the conversation open.

Language & Semantics

For someone who is neurodivergent, language and semantics are often very important. Autistics are often quite literal which can easily lead to miscommunication. A lifetime of misinterpretations can make lack of clarity and miscommunication feel dangerous and contribute to communication-based trauma.

Neurotypical clinicians may experience a neurodivergent patient questioning rules or identifying discrepancies in action and words used as avoidance, non-compliant, willful, or disruptive. It’s important to recognize that this is not the case, and that clarification and understanding are important for building safety.

Clinicians should remember to be direct, detailed, and specific with language. Do not assume implied meaning is understood.

Executive Functioning

People who are neurodivergent often struggle with executive functioning.

Executive dysfunction can show up in both obvious and subtle ways in the eating disorder and in treatment. This can be a source of shame for many neurodivergent individuals.

They may become quite frustrated with themselves for not being able to do a task. The shame can then fuel the eating disorder and be perpetuated by treatment when neurotypical expectations and masking are encouraged. This then becomes another of the many maintaining mechanisms of the eating disorder.

Someone may become hyper focused on something and then forget about eating. This can be where the ARFID subtype, lack of interest in eating, comes in.

Task switching can also be difficult for this population, such as shifting from one therapy group to another or if they stop a task to eat, they may experience difficulty going back to what they were doing.

When tasks are not completed, explore the barriers with your client. After identifying the root of the issue, work together to find practical solutions that fit the individual’s capacity in the moment.

Neurodivergent individuals often experience heightened sensory sensitivity, as well. Dealing with sensory input can be exhausting as it takes a lot of energy. Clinicians must work together to reduce shame and stigma surrounding executive dysfunction.

Conclusion

Whether you’re treating patients or seeking treatment for yourself or a loved one, make sure the practice you work for or are considering is educated on neurodiversity and open to creative approaches. For patients, if you have received accommodations or services at school or at work that have been helpful, please share these with your team. Everyone deserves an accessible path to recovery.

Helpful resources:

Autistic Self Advocacy Network (autisticadvocacy.org)

Instagram – Let’s Get Following!

- @thearticulateautistic

- @edadhd_therapist

- @weareunmasked

- @fedupcollective

- @autieselfcare

- @livedexperiencededucator